The Statue of Liberty

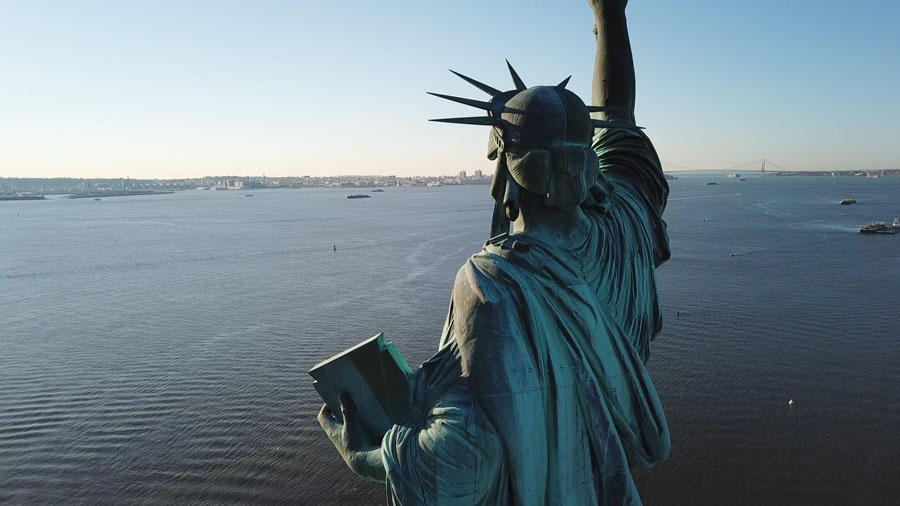

Standing majestically in New York Harbor, just a short distance from Long Island’s western shores, the Statue of Liberty remains one of the most recognizable symbols of freedom in the world. This colossal copper monument, officially titled “Liberty Enlightening the World,” has welcomed millions of visitors and immigrants to American shores since her dedication on October 28, 1886. For Long Islanders, Lady Liberty represents not just a nearby attraction but an integral part of the region’s history and identity-a beacon visible from various points along the island’s coastline and intimately connected to the immigrant heritage that shaped the New York metropolitan area.

The statue’s presence in Upper New York Bay makes her a natural destination for those exploring the Long Island and New York City area. Rising 305 feet from ground to torch, with the statue itself measuring 151 feet tall, this remarkable engineering achievement continues to inspire visitors from around the world.

Historical Origins: A Gift from France

The Statue of Liberty’s story begins not in America but in France, at a dinner party in 1865 near Paris. Édouard René de Laboulaye, a prominent French political thinker, U.S. Constitution expert, and abolitionist, first proposed the idea of a monument for the United States. Known as the “Father of the Statue of Liberty,” Laboulaye was a passionate supporter of President Abraham Lincoln and the Union cause during the American Civil War.

Laboulaye believed that the recent Union victory, which reaffirmed American ideals of freedom and democracy, could serve as inspiration for France’s own democratic aspirations. As president of the French Anti-Slavery Society, he viewed the passage of the 13th Amendment in 1865 as a milestone proving that justice and liberty for all was possible. His proposal to create a monument honoring the United States served a dual purpose: commemorating the Franco-American alliance during the Revolutionary War while inspiring the French people to call for democracy in the face of their own repressive monarchy under Napoleon III.

Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi’s Artistic Vision

Among the guests at that fateful 1865 dinner was sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, who would transform Laboulaye’s vision into reality. Born in 1834 in Colmar, France, Bartholdi had studied architecture, painting, and drawing before focusing entirely on sculpture. He made his Paris Salon debut before turning 20 and would go on to become one of France’s most celebrated sculptors.

Bartholdi envisioned a massive statue of a woman holding a torch burning with the light of freedom. His design drew inspiration from Libertas, the ancient Roman goddess of liberty, while incorporating modern neoclassical elements. The sculptor spent years refining his vision, creating numerous models at different scales to perfect the proportions. He employed a sophisticated scaling system using plaster models at ratios of 1:16, 1:4, and finally full scale to maintain accurate proportions during enlargement.

In September 1875, Laboulaye officially announced the project and formed the Franco-American Union as its fundraising arm. The agreement was straightforward: the French people would finance the statue itself, while Americans would pay for the pedestal upon which it would stand.

Design and Symbolism: Every Detail Tells a Story

The statue’s crown features seven rays projecting outward, representing the seven continents and seven oceans of the world, symbolizing the universal nature of freedom. This design choice emphasizes that liberty is not confined to America but is a concept meant for all humanity. The crown contains 25 windows that visitors who climb to the top can peer through, offering breathtaking views of New York Harbor.

In Lady Liberty’s raised right hand, she holds a torch covered in 24-karat gold leaf. The torch represents enlightenment-the idea that knowledge and freedom illuminate the path to progress. Symbolically, the flame signifies lighting the way to liberty and guiding people toward justice and democracy.

In her left hand, the statue holds a tabula ansata (a tablet evoking the concept of law) inscribed with “JULY IV MDCCLXXVI”—the date of the Declaration of Independence in Roman numerals. Though Bartholdi greatly admired the U.S. Constitution, he chose to inscribe the Declaration’s date to associate American independence with the broader concept of liberty.

Hidden beneath her flowing robes at Lady Liberty’s feet lies a powerful symbol many visitors never notice: broken chains and shackles. These represent freedom from oppression and tyranny, with the statue’s right foot raised as if stepping forward away from bondage. This detail reflects the monument’s connection to the abolition of slavery and the broader struggle for human rights.

The Classical Design

Bartholdi’s design philosophy emphasized broad, simple surfaces with bold, clear lines. He understood that for a colossal statue to be effective, details had to be simplified and forms exaggerated to remain visible from great distances. The classical contrapposto pose—with one foot raised and weight shifted—creates a sense of both stability and forward movement, symbolizing the dynamic nature of liberty itself.

Construction: A Marvel of Engineering

While Bartholdi provided the artistic vision, the statue required revolutionary engineering to stand against the harsh weather conditions of New York Harbor. Initially, architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc proposed the internal structure, but after his death in 1879, Alexandre-Gustave Eiffel was brought in to complete the project.

Eiffel, who would later design the iconic Eiffel Tower in Paris, created an ingenious solution. He designed a tall central iron pylon standing 92 feet high, which serves as the primary support structure. This pylon is connected to a secondary skeletal framework that roughly follows the statue’s shape. Rather than creating a rigid structure, Eiffel designed a flexible system that allows the copper skin to move independently of the iron framework.

This revolutionary “curtain wall” construction meant the exterior skin was not load-bearing but instead supported by the interior framework. Flat metal bars bolted at one end to the pylon and at the other to the copper skin create flexible suspension, allowing the statue to adjust to winds and temperature changes without tearing itself apart. The statue can sway up to 3 inches in 50-mile-per-hour winds, while the torch may move as much as 6 inches.

The Repoussé Technique

The statue’s copper “skin” consists of approximately 300 individual sheets, each only about 3/32 of an inch thick-roughly the thickness of two pennies. These copper sheets were shaped using an ancient metalworking technique called repoussé, in which heated sheets of copper were hammered against wooden molds to create the desired forms.

This technique, while labor-intensive, created a structure that was remarkably light for its size—the entire copper skin weighs only 62,000 pounds (31 tons), while the iron framework weighs 250,000 pounds (125 tons). The use of repoussé was essential for creating a monument that could be disassembled, shipped across the Atlantic Ocean, and reassembled in America.

Construction in Paris

The statue was built entirely in France between 1875 and 1884. Construction took place at workshops in Paris, where different sections were assembled as they were completed. By 1882, the statue had been completed up to the waist, and Bartholdi celebrated by inviting reporters to lunch on a platform built within the statue. The completed statue stood tall above the Parisian rooftops, visible throughout the city, before being disassembled for its journey to America.

On July 4, 1884, France formally presented the Statue of Liberty to the United States in a ceremony in Paris, with U.S. Ambassador to France Levi P. Morton accepting on behalf of the American people.

Building the Pedestal: The American Challenge

While the French built the statue, Americans faced their own challenge: constructing a suitable pedestal. In 1881, the New York committee commissioned architect Richard Morris Hunt to design the base. Hunt, the first American to attend the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, was one of the most prominent architects of the Gilded Age.

Hunt’s pedestal design incorporates elements of classical architecture, including Doric portals, along with influences from Aztec architecture. The design forms a truncated pyramid, measuring 62 feet square at the base and 39.4 feet at the top, rising to a total height of 89 feet. Hunt intended the pedestal to complement rather than compete with the statue itself, creating harmony between base and sculpture.

The pedestal sits within the walls of Fort Wood, a disused military installation constructed between 1807 and 1811 in the shape of an eleven-point star. This star-shaped fort, built to defend New York Harbor during the War of 1812, provided a dramatic and symbolic foundation for the monument.

The Funding Crisis and Joseph Pulitzer’s Campaign

Financing the pedestal proved more difficult than anticipated. By 1884, with construction of the pedestal underway, the project ran out of money. Public interest had waned, and fundraising efforts stalled despite the statue already waiting in crates after arriving in New York in June 1885.

Enter Joseph Pulitzer, publisher of the New York World. Pulitzer launched an aggressive fundraising campaign in his newspaper, promising to publish the name of every donor regardless of the amount given. His editorials shamed wealthy New Yorkers for their lack of support while celebrating donations from working-class Americans and immigrants. The campaign succeeded spectacularly-by August 11, 1885, the World announced that $102,000 had been raised from 120,000 donors, with 80 percent of contributions being less than one dollar.

Construction of the pedestal was completed in April 1886, and the statue’s reassembly began immediately.

Dedication and Early History

On October 28, 1886, over one million people gathered to witness the dedication of the Statue of Liberty. Despite rainy weather, the celebration included parades both on land and at sea. Firemen, soldiers, and veterans-including the 20th Regiment of U.S. Colored Troops-marched down Broadway to the sounds of 100 brass bands, cannons, and sirens.

A flotilla of ships decorated in red, white, and blue formed a naval parade to Bedloe’s Island (later renamed Liberty Island). Bartholdi himself was stationed inside the statue’s crown, awaiting the signal to unveil the monument. In a moment of confusion, he released the French flag covering the statue’s face prematurely, in the middle of Senator William M. Evarts’ speech. Cannons thundered, brass bands roared, and steam whistles blew from hundreds of ships in the harbor, drowning out the senator’s words but creating an unforgettable celebration.

President Grover Cleveland accepted the monument on behalf of the American people, declaring: “We will not forget that Liberty has here made her home; nor shall her chosen altar be neglected“.

From Copper to Green: The Patina

When first erected, the Statue of Liberty gleamed with the reddish-brown color of new copper. However, within two decades, chemical reactions with air, water, and pollution transformed the statue’s color to the iconic blue-green patina we recognize today.

This color change results from copper oxidation. First, the copper reacted with oxygen to form pinkish-red cuprite, which further oxidized to black tenorite. Sulfur dioxide in the atmosphere reacted with water to form sulfuric acid, which combined with tenorite and water to create blue-green brochantite and green antlerite. Salt spray from the harbor contributed chloride ions that reacted with brochantite to form olive-green atacamite. By 1906, the statue’s distinctive green patina was fully formed.

Far from being damage, this patina acts as a protective layer, preventing further corrosion and preserving the copper underneath—one reason the statue has survived over 135 years of exposure to harsh maritime weather.

Emma Lazarus and “The New Colossus”

In 1883, poet Emma Lazarus wrote “The New Colossus” to raise funds for the pedestal construction. Initially hesitant to contribute, Lazarus was convinced by writer Constance Cary Harrison that the statue would hold great significance for immigrants arriving in New York Harbor.

Lazarus, a Jewish-American writer who worked extensively with Jewish refugees fleeing pogroms in eastern Europe, saw an opportunity to express her empathy for immigrants in terms of the statue. Her sonnet contrasts the ancient Colossus of Rhodes—”the brazen giant of Greek fame, with conquering limbs astride from land to land”—with a new kind of colossus: a “mighty woman with a torch” who is not a symbol of conquest but of welcome.

The poem’s most famous lines appear in the sestet:

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

While the poem was read at the pedestal fundraising exhibition opening in 1883, it was largely forgotten after the statue’s dedication in 1886. In 1901, Lazarus’s friend Georgina Schuyler began an effort to memorialize both the poet and her work. In 1903, a bronze plaque bearing the poem’s text was mounted inside the pedestal, where it remains today.

“The New Colossus” fundamentally transformed the statue’s meaning. Originally conceived as a symbol of Franco-American friendship and republican ideals, the statue became the “Mother of Exiles”-a symbol of immigration, refuge, and the American dream.

Ellis Island and Immigration: Gateway to America

The statue’s transformation into an immigration symbol gained powerful reinforcement when Ellis Island Immigration Station opened in 1892, just seven years after the statue’s dedication. Located less than a mile from Liberty Island, Ellis Island became the nation’s busiest immigration processing center, operating from 1892 to 1954.

During those 62 years, nearly 12 million immigrants passed through Ellis Island’s halls. For most, the Statue of Liberty was the first sight they encountered upon arriving in America-a towering symbol of the freedom and opportunity they sought. First and second-class passengers were inspected briefly aboard ship, but third-class or “steerage” passengers were ferried to Ellis Island for detailed medical and legal inspection.

The connection between Lady Liberty and Ellis Island created an enduring association. The statue came to represent not just abstract ideals of freedom but the concrete experience of immigration—hope, fear, determination, and new beginnings. For millions of Americans today, the statue evokes family stories of ancestors who passed beneath her gaze on their way to building new lives.

The Torch: Original and Restored

The statue’s torch has perhaps the most complicated history of any element of the monument. Bartholdi’s original design called for a flame made of solid copper covered in thin gold leaf, with floodlights on the torch’s balcony to illuminate it. However, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers vetoed this plan, fearing the lights would blind ship pilots. Instead, Bartholdi cut portholes in the flame and placed lights inside-but these proved inadequate, and the statue failed to function as the lighthouse some had envisioned.

In 1916, sculptor Gutzon Borglum (who would later create Mount Rushmore) redesigned the torch, replacing the copper with amber glass panels and internal electric lights to make it more visible. Unfortunately, this modification allowed water to leak into the statue’s arm, causing significant damage over the decades.

The Black Tom Explosion

On July 30, 1916, German saboteurs detonated explosives at the Black Tom munitions depot in Jersey City, just across the harbor from Liberty Island. The massive explosion-one of the largest non-nuclear blasts in history—showered the statue with shrapnel and caused structural damage to the arm and torch. After this incident, public access to the torch was permanently closed for safety reasons.

The 1986 Replacement

During the statue’s centennial restoration project (1984-1986), engineers determined that the damaged torch was beyond repair. They created an exact replica of Bartholdi’s original design, this time including the gold leaf covering he had originally envisioned but couldn’t afford. The new torch, covered in 24-karat gold leaf, reflects sunlight during the day and is illuminated by external floodlights at night.

The original torch, weighing 3,600 pounds and standing 16 feet tall, was placed on display in the pedestal’s museum. In 2018, it was moved to the new Statue of Liberty Museum, where it serves as the centerpiece of the Inspiration Gallery, visible to all island visitors.

The 1980s Restoration: A Monument in Distress

By the early 1980s, nearly a century of weather, pollution, and visitor traffic had taken their toll on Lady Liberty. The torch was beyond repair, the crown’s rays needed strengthening, and pieces of the statue’s face, hair, and gown required attention. Most critically, the iron armature bars that connected the copper skin to Eiffel’s framework were corroding, creating galvanic corrosion that threatened the statue’s structural integrity.

An Unprecedented Restoration Effort

In 1982, President Ronald Reagan appointed Lee Iacocca, chairman of Chrysler Corporation, to head the Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation. The Foundation led a private sector fundraising effort while working with the National Park Service to plan and oversee the restoration-ultimately raising $87 million in what remains one of the most successful public-private partnerships in American history.

In 1984, scaffolding was erected around the statue, and work began. A team of French and American architects, engineers, and conservators implemented unprecedented restoration techniques. Workers repaired holes in the copper skin, removed layers of paint from the interior, and replaced approximately 1,800 corroding iron armature bars with stainless steel bars to prevent future galvanic corrosion.

The entire restoration took two years, with nearly 1,000 laborers contributing to the effort. The work was completed in time for the statue’s centennial celebration.

Liberty Weekend: July 4, 1986

The restored Statue of Liberty was unveiled during “Liberty Weekend,” a four-day celebration from July 3-6, 1986. President Reagan and French President François Mitterrand attended the festivities, which included fireworks, a parade of tall ships in the harbor, and celebrations broadcast to 1.5 billion people in 51 countries. On July 5, a new Statue of Liberty exhibit opened in the pedestal’s base.

The restoration proved remarkably successful. Inspections ten years later confirmed that all previous corrosion impacts had been reversed and no new problems had developed.

Hurricane Sandy and Resilience

On October 29, 2012, Superstorm Sandy struck the New York area with devastating force. The statue had just reopened on October 28-its 126th birthday-after the year-long centennial restoration, only to close again the next day.

While Lady Liberty herself remained unscathed, Liberty Island suffered catastrophic damage. The 14-foot storm surge submerged approximately 75 percent of the 12-acre island. The ferry docks were destroyed, electrical and sewage systems were inundated, and the walkways surrounding the statue were severely damaged. Equipment, transformers, and backup generators were rendered inoperative.

The superintendent’s residence on the island was “essentially destroyed“. The serpentine dock that had been redesigned as part of earlier improvements was damaged, the seawall began detaching, and sections of fencing were torn away.

The Recovery

The National Park Service, FEMA, and other federal agencies immediately began working on repairs. The restoration effort focused not just on rebuilding but on creating more resilient infrastructure. The promenade around the island was reconstructed using interlocking, full-thickness brick pavers secured so that future storm surges wouldn’t dislodge them individually. Over 53,000 square feet of the Liberty Island promenade were replaced, providing 2,000 linear feet of improved public access.

The statue reopened to visitors on July 4, 2013-Independence Day-in a ceremony celebrating not just the monument but New York’s resilience and recovery. Superintendent David Luchsinger, speaking at the reopening, said with a laugh: “I don’t know about you, but I’m getting a little bit tired of reopening and closing the Statue of Liberty. I think this time we’ll just leave it alone”.

Visiting the Statue Today: Access and Tickets

The Statue of Liberty welcomes approximately 3 to 4 million visitors annually, making it one of the most visited attractions in the United States. The monument is accessible only by ferry, with Statue City Cruises providing the sole authorized ferry service departing from Battery Park in Manhattan and Liberty State Park in Jersey City.

All ferry tickets include round-trip transportation, access to both Liberty Island and Ellis Island, and entry to the museums on both islands. Self-guided audio tours are available in 12 languages, with family-friendly, American Sign Language, and audio descriptive versions also offered.

Ticket Types and Access Levels

Visitors can choose from three ticket types, each offering different levels of access:

- Reserve Ticket (Ground Access): Includes ferry transportation and access to the grounds of Liberty Island and Ellis Island, plus both museums. Visitors can explore the island and view the statue from outside but cannot enter the pedestal or statue.

- Pedestal Reserve Ticket: Includes everything in the Reserve Ticket plus access to the pedestal observation decks. Visitors can enter Fort Wood’s star-shaped walls and take an elevator to viewing platforms that offer spectacular views of the New York Harbor and city skyline. The pedestal level also features viewing panels that allow visitors to look up into the statue’s interior framework.

- Crown Reserve Ticket: The most exclusive access, allowing visitors to climb 162 narrow, winding steps from the pedestal to the crown itself—a total of 393 steps from ground level. The crown contains 25 windows offering unparalleled views. Crown tickets must be reserved well in advance (sometimes months ahead) and are limited to four tickets per transaction. Children must be at least 42 inches tall to access the crown.

Security and Practical Considerations

Following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, the statue was closed for security reasons. The base reopened in 2004, the pedestal in 2009, and the crown finally reopened on July 4, 2009, with enhanced security measures.

Today, all visitors must pass through airport-style security screening. Many items are prohibited inside the statue, including large bags, backpacks, and camera tripods. Lockers are available for rent (requiring a 25-cent deposit) near the screening facility.

The climb to the crown is strenuous-approximately equivalent to climbing a 27-story building in an enclosed, non-air-conditioned space. Interior temperatures can be 20 degrees higher than outside, especially in summer. The National Park Service recommends that visitors drink water before ascending and be free of physical or mental conditions that would impair their ability to complete the climb.

The Museums

- The Statue of Liberty Museum, which opened in May 2019, is a 26,000-square-foot facility accessible to all island visitors regardless of ticket type. The museum features the original torch as its centerpiece in the Inspiration Gallery, along with exhibits on the statue’s construction, history, and cultural significance. Floor-to-ceiling glass panels offer visitors an up-close view of the copper torch that Lady Liberty held for nearly a century.

- The Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration tells the story of the 12 million immigrants who passed through the immigration station. The museum features restored spaces, historical artifacts, and the American Immigrant Wall of Honor, which contains the names of over 700,000 immigrants.

The Statue’s Connection to Long Island

For Long Islanders, the Statue of Liberty occupies a special place in the regional landscape. While located in Upper New York Bay, the statue is visible from various points along western Long Island, particularly from elevated areas and waterfront locations. The monument stands as a constant reminder of the region’s immigrant heritage and its connection to New York Harbor’s history.

Many Long Island families have personal connections to Ellis Island, with ancestors who passed beneath Lady Liberty’s gaze upon arriving in America. The statue represents not just national history but family history for countless Long Islanders whose grandparents and great-grandparents entered the country through New York Harbor.

Transportation from Long Island

Long Islanders can reach the Statue of Liberty via several routes. The most common involves taking the Long Island Rail Road to Penn Station in Manhattan, then traveling by subway to Battery Park, where Statue City Cruises departs. The journey typically takes between 2 to 3 hours from central Long Island locations.

Alternatively, visitors can drive to Jersey City’s Liberty State Park, where another ferry departure point offers free parking and somewhat shorter lines than the Manhattan location. This option can be particularly convenient for Long Island residents who prefer driving and want to avoid Manhattan traffic.

Cultural Impact and Legacy

The Statue of Liberty has become one of the most referenced symbols in global popular culture. She appears in countless films, from Alfred Hitchcock’s Saboteur (1942) to The Day After Tomorrow (2004). The statue’s most iconic film appearance may be the final scene of Planet of the Apes (1968), where the half-buried monument reveals that the alien planet is actually post-apocalyptic Earth—an image that demonstrates the statue’s power as instant visual shorthand for human civilization.

In advertising, the statue’s image appears on products worldwide, from tourist souvenirs to luxury goods, making her one of the most commercially reproduced symbols in history. Every major disaster film seems to include a scene of Liberty damaged or destroyed, using her destruction to symbolize catastrophe precisely because she represents endurance and freedom.

UNESCO World Heritage Site

In 1984, the Statue of Liberty was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, recognizing her “outstanding universal value” to humanity. UNESCO acknowledged the statue under Criterion (i) as “a masterpiece of the human spirit,” highlighting the collaboration between Bartholdi and Eiffel that brought together art and engineering in a revolutionary way.

Under Criterion (vi), UNESCO recognized the statue’s symbolic value, noting that it represents not just Franco-American friendship but has become “a highly potent symbo-inspiring contemplation, debate, and protest-of ideals such as liberty, peace, human rights, abolition of slavery, democracy, and opportunity”.

A Living Symbol

What makes the Statue of Liberty truly remarkable is how her meaning has evolved while remaining relevant. Originally conceived as a symbol of republican democracy and Franco-American friendship, she became the Mother of Exiles welcoming immigrants. She represents American values, yet people worldwide claim her as a symbol of universal human rights. She stands for establishment ideals yet has been embraced by protesters and activists demanding change.

This flexibility-the ability to mean different things to different people while maintaining core associations with freedom and hope-explains the statue’s enduring power. She belongs to no single political party or ideology but to all who believe in human dignity and liberty.

Fun Facts and Trivia

- Lady Liberty would wear size 879 shoes if she could shop in American stores

- The statue is struck by lightning approximately 600 times every year

- Her waist measures 35 feet around

- Each fingernail weighs about 100 pounds

- The seven spikes on her crown each weigh approximately 150 pounds

- If the statue could walk, her stride would be 25 feet long

- The index finger alone is 8 feet long

- The tablet she carries weighs approximately 150 pounds and measures 23 feet 7 inches tall

- Bartholdi’s mother, Charlotte, is said to have been the model for Lady Liberty’s face

- The statue was the tallest iron structure in the world when completed in 1886

- It took 21 years from conception to dedication to complete the project

Visiting Tips for Long Islanders

- Book in Advance: Crown tickets sell out months ahead, and even pedestal tickets can be limited during peak season. Reserve tickets as early as possible, especially for summer visits.

- Arrive Early: Security screening and ferry boarding take time. Plan to arrive at least 30 minutes before your scheduled ferry departure.

- Consider Off-Season: Fall and winter visits offer shorter lines and smaller crowds, though weather can be less predictable.

- Bring Minimal Items: Security restrictions prohibit large bags. Bring only essentials, and be prepared to rent a locker for items not allowed in the statue.

- Wear Comfortable Shoes: Even with ground access only, you’ll be walking extensively. Crown access requires climbing 393 steps.

- Plan a Full Day: To experience both Liberty Island and Ellis Island thoroughly, including the museums, plan for at least 4-5 hours.

- Check the Weather: The statue can close due to extreme weather, and much of the experience is outdoors.

An Enduring Beacon

For nearly 140 years, the Statue of Liberty has stood watch over New York Harbor, her torch raised high as a beacon of freedom. For Long Islanders and all who call the New York region home, she represents more than history or architecture-she embodies the ideals that continue to draw people to American shores and the promise of liberty that resonates across generations.

Whether viewed from afar across the water or experienced up close through a visit to Liberty Island, the statue remains what Bartholdi and Laboulaye envisioned: a light enlightening the world, a symbol of the best aspirations of humanity, and a reminder that the struggle for freedom and dignity continues for every generation. As Emma Lazarus wrote, Lady Liberty lifts her lamp beside the golden door, welcoming all who seek the opportunity to build a better life in freedom.

The Statue of Liberty belongs to everyone who cherishes liberty-and that includes the people of Long Island, whose shores she has graced for over a century, whose ancestors she welcomed to a new world, and whose children will continue to find inspiration in her enduring message of hope anchildren will continue to find inspiration in her enduring message of hope and freedom.

| Key Facts & Details — Statue of Liberty | Details |

|---|---|

| Official Name | Liberty Enlightening the World |

| Type | National Monument & UNESCO World Heritage Site (1984) |

| Location | Liberty Island, Upper New York Bay, New York, NY 10004 |

| GPS | 40.689249, −74.044500 |

| Height | 305 ft (ground to torch); statue alone 151 ft |

| Materials | Copper repoussé skin over iron (now stainless-steel) armature |

| Designer / Engineer | Sculptor: Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi · Structural: Gustave Eiffel (after Viollet-le-Duc) |

| Concept & Funding | Proposed by Édouard de Laboulaye (1865); France funded statue, U.S. funded pedestal |

| Pedestal Architect | Richard Morris Hunt (within Fort Wood’s 11-point star) |

| Construction | Built in Paris 1875–1884; gifted July 4, 1884; assembled in NY 1885–1886 |

| Dedication | October 28, 1886 (Pres. Grover Cleveland) |

| Symbolism | Torch = enlightenment; tablet dated JULY IV MDCCLXXVI; 7 crown rays = continents & oceans; broken chains at feet = freedom from oppression |

| Patina | Natural copper oxidation (fully formed by ~1906) that protects the metal |

| Major Restorations | Centennial restoration 1984–1986 (new gold-leaf torch); island resilience work post-Hurricane Sandy (2012–2013) |

| Access Levels | Reserve (grounds & museums) · Pedestal Reserve (elevator/observation decks) · Crown Reserve (162 steps from pedestal; total 393 from ground; limited tickets) |

| Annual Visitors | ~3–4 million |

| Ferry & Tickets | Statue City Cruises from Battery Park (NYC) and Liberty State Park (NJ); round-trip includes Liberty & Ellis Islands + museums |

| Museums | Statue of Liberty Museum (original torch, opened 2019) · Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration |

| Long Island Note | Visible from western LI shores; typical LI trip: LIRR → Penn Station → subway to Battery Park (~2–3 hrs). Driving option via Liberty State Park (often easier parking). |

| Good to Know | Airport-style security; restricted items; small lockers available; crown climb is strenuous & warm; crown height minimum 42″ for kids |

| Cultural Impact | “Mother of Exiles” (Emma Lazarus, The New Colossus); global icon featured in film, art, and literature |

| Managing Agency | U.S. National Park Service (Statue of Liberty National Monument) |

| Websites | NPS: nps.gov/stli · Tickets: cityexperiences.com/new-york/city-cruises/statue |