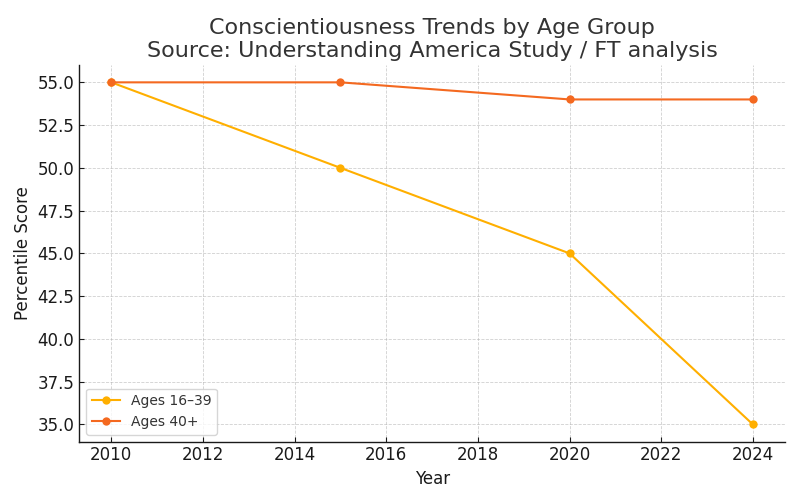

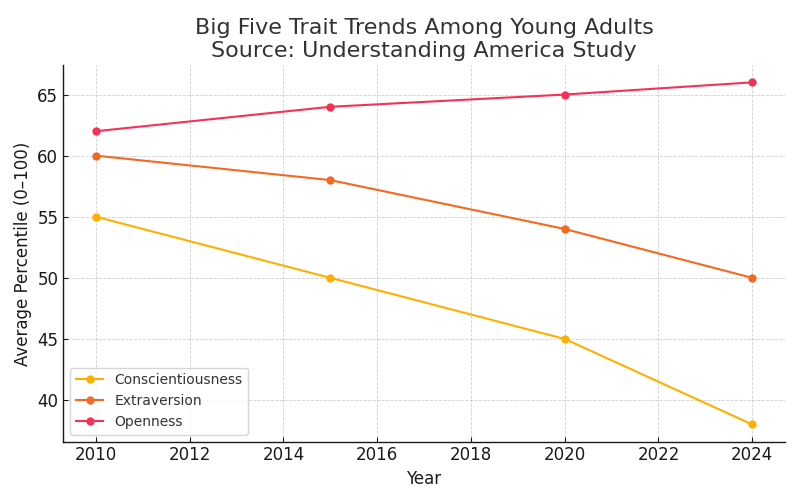

NEW YORK, NY – A new analysis of long‑running U.S. survey data reports a steep decline in conscientiousness among younger Americans over the past decade, intensifying concerns about attention, follow‑through, and self‑control in the age of always‑on digital media. The findings, published by the Financial Times using the University of Southern California’s Understanding America Study (UAS), show the biggest drops among people ages 16 to 39, while older adults have seen little change.

Conscientiousness – one of the “Big Five” personality traits – captures tendencies such as persistence, planning, and reliability. It generally changes slowly across the life course, which makes the reported 2010s‑to‑2020s slide notable. Aggregators and tech outlets quickly amplified the FT’s charts, highlighting potential links between heavy smartphone use, streaming platforms, and a broader shift from in‑person commitments to digital engagement.

Independent research provides context. Peer‑reviewed studies tracking Americans before and after the pandemic found small early shifts followed by broader 2021–2022 declines in several traits – including conscientiousness, suggesting environmental pressures beyond any single technology may be involved. Those changes were modest in size but meaningful at population scale.

What remains unresolved is causation. The FT analysis points to smartphones and streaming as likely contributors given their ubiquity and design for constant engagement, but it also acknowledges other forces, from pandemic disruptions to evolving social norms, may be driving or amplifying the trend. Establishing cause would require longitudinal designs that directly link usage patterns to later personality change while controlling for confounders.

Why it matters: declines in conscientiousness are associated in prior literature with weaker educational, workplace, health, and financial outcomes. Long‑running studies have repeatedly connected higher conscientiousness with better saving behavior and long‑term planning, underscoring the potential consequences if the downtrend persists.

For now, the evidence is strongest on what is happening – a measurable drop in conscientiousness among younger cohorts – than on why it is happening. Researchers say the next step is to pair behavioral data (screen time, app categories, notifications) with repeated personality measures over time to test the smartphone‑specific hypothesis more directly.

Q&A: Smartphones, Personality Change, and the Decline in Conscientiousness

Q: What is conscientiousness, and why is it important?

A: Conscientiousness is one of the “Big Five” personality traits. It reflects responsibility, organization, self-control, and the ability to follow through on commitments. Higher conscientiousness is strongly linked to better educational, career, financial, and health outcomes.

Q: What does the new data show?

A: Analysis from the Financial Times using the University of Southern California’s Understanding America Study found a sharp drop in conscientiousness among Americans aged 16 to 39 over the past decade. Older adults have seen little to no change.

Q: How steep is the decline?

A: For younger adults, average conscientiousness scores have fallen from above the national average to around the 30th percentile – an unusually rapid change for a personality trait that typically evolves slowly over a lifetime.

Q: Are smartphones to blame?

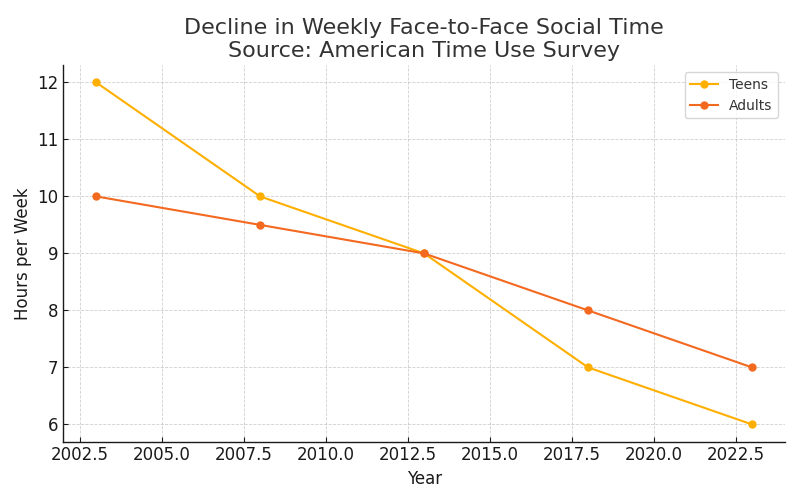

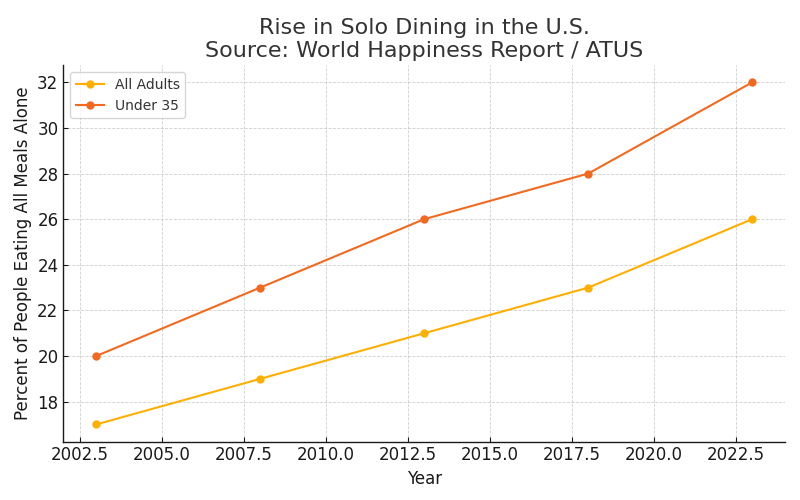

A: The analysis suggests smartphones and streaming platforms are likely contributors, given their ability to capture attention and reduce face-to-face interaction. However, researchers stress that multiple factors, including pandemic disruptions and shifting social norms, could also be influencing the trend. Direct causation has not yet been proven.

Q: What are the possible effects of this change?

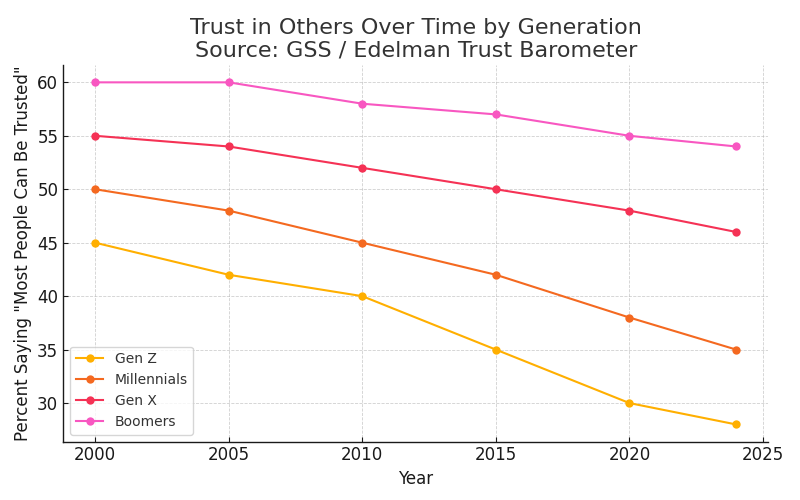

A: Lower conscientiousness can impact work performance, academic achievement, personal relationships, and long-term planning. Over time, it can also correlate with lower income, weaker health outcomes, and less social trust.

Q: How do smartphones potentially influence personality?

A: Features like endless scrolling, algorithm-driven content, constant notifications, and instant feedback loops can encourage impulsivity, reduce attention spans, and make it easier to abandon commitments in favor of immediate gratification.

Q: Has this kind of societal shift happened before?

A: The Financial Times compared it to the arrival of the printing press, which reshaped human culture over centuries. The difference now is speed—smartphones have transformed behavior and attention in just over a decade, giving society little time to adapt.

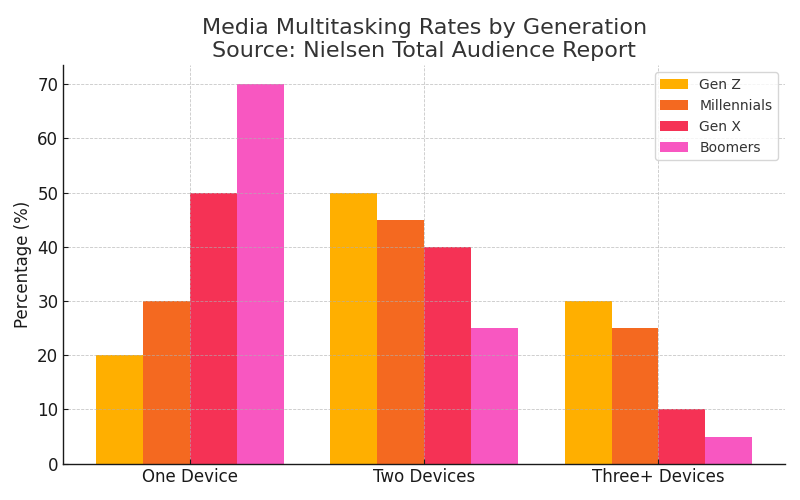

Q: What is Gen Z and Millennials?

A: Gen Z refers to people born roughly between 1997 and 2012 (currently in their teens to mid-20s). They grew up with smartphones, social media, and high-speed internet as a normal part of daily life.

Millennials are those born roughly between 1981 and 1996 (now in their late 20s to early 40s). They experienced the transition from pre-internet life to the digital age and were among the first to adopt smartphones and social media as young adults.

Q: Can this trend be reversed?

A: Solutions like screen-time limits, app timers, and “digital detox” challenges may help individuals, but experts say systemic change – such as altering platform incentives away from pure engagement – would be needed for large-scale improvement.

Q: What should people do now?

A: The first step is recognition – acknowledging that attention is a finite resource and protecting it as intentionally as possible. This may mean setting personal tech boundaries, prioritizing in-person interactions, and seeking activities that require sustained focus.